Forty years ago, a small deaf mime company performed at Melbourne’s Pram Factory. It performed for six nights in August 1975, and again the next year. Then it dropped out of sight.

Forty years ago, a small deaf mime company performed at Melbourne’s Pram Factory. It performed for six nights in August 1975, and again the next year. Then it dropped out of sight.

In 1974, the National Theatre of the Deaf from the United States toured Australia. The group that was to become known as Earforce went to see it. The NTD performance was a farce. This professional deaf theatre company did nothing for those who could neither hear nor follow sign language. I remembered feeling baffled and bewildered. I remembered a subtle message: because we spoke, because we didn’t know signs, we weren’t really deaf, and therefore we didn’t count.

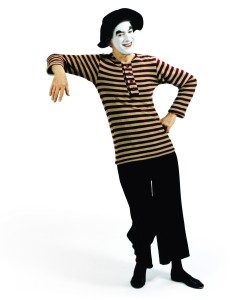

But we thought we could act. At the time we had no connection with the Adult Deaf Society of Victoria; none of us knew sign language. The one group that gave us a place to meet and so start drama classes was Better Hearing Australia. The drama classes were as much social occasions as they were a study of stagecraft. The director, Sandra Shotlander, could see that, but she also knew we had something else, something that was enough to justify a grant from the Australian Arts Council, finding a choreographer, devising a program and rehearsals, and a booking of theatre space at the Pram Factory in Carlton.

This astonishing theatre space was one of the centres of Australian alternative theatre. It was nothing like traditional, mainstream theatre; it was dedicated to original and Australian works. It was 1975, the Whitlam Government was supporting the arts, and anything could be possible.

The show was a bit over an hour, and featured numerous short pieces. Some reflected deafness, some did not. Some sketches could have been inspired by Benny Hill, but at least there was a lot of audience laughter, for the right reasons, I was sure. Other sketches were quite moving.

Mime was the foundation, and I was never sure that technically we were that good. People told us that we were. But I was not convinced. I had wondered whether critics were being too kind. Were they gripped by a disabled arts syndrome that renders critics unable to tell you if your performance was, basically, crap? Yet I do remember the joy of some people in the audience who came to us afterwards.

we were. But I was not convinced. I had wondered whether critics were being too kind. Were they gripped by a disabled arts syndrome that renders critics unable to tell you if your performance was, basically, crap? Yet I do remember the joy of some people in the audience who came to us afterwards.

There was apparently a new nightclub that was interested in booking us. A nightclub? Where people smoked cigarettes and drank alcohol? Nothing came of that.

Mime and Mumbles performed elsewhere, at the Augustine Centre in Hawthorn, and at the then Victorian School for Deaf Children. And there was even one sketch performed for the 1976 deafness appeal telethon, one that was met by an embarrassed silence. I felt that standards were slipping, and especially, I wanted to do theatre that was darker and gutsier. That was never going to happen.

I was being overly harsh. The company kept some momentum, found a new director, and rehearsed for a second season. I sensed more of the same, thought there was no progress, and I dropped out. Once again the company performed a program called ‘Chapters of Life’ at the Pram Factory. It was another six performances, and again it had an impact.

Soon afterwards, we talked more. I remember talk of experimental mime. But that was as far as it went, and the company quietly folded. Many of the company members were in relationships, and within a few years marriages eventuated and children were born. Life had very different priorities.

The Pram Factory has long been demolished. There is no reference to Mime and Mumbles in its history. The only references in Google are to a couple of very short newspaper items, and a mention in Sandra Shotlander’s theatre career. There remain some photos, and possibly some memorabilia is lying around; perhaps there is a tattered program in a box in someone’s garage or at the back of someone’s old filing cabinet.

Mime and Mumbles was a curious dip into a very different creative pursuit. The way it explored deafness put it a notch above traditional amateur show, and I glimpsed the possibilities of exciting, even radical and innovative theatre. But that needed performers of a different calibre.

Nonetheless the memories I have are good ones. I remember bright stage lights, a warm glow rising from the audience in a small performing space, the tang of grease paint, and the fascinated hearing people we attracted. And I remember the gatherings and parties after each performance, where we gossiped and laughed and talked long into the night of all the things that could become possible.

Leave a Reply