An executive of a disability organisation who doesn’t think much of the value of “lived experience” of people with disabilities is unaware of the one thing everyone with a disability knows about. It’s something MICHAEL UNIACKE would like to see in a flag.

THE IDEA OF “LIVED experience” of disability makes Phil Hayes-Brown nervous. Writing in the Melbourne ‘Age’ some weeks ago, he objected to disability advocates who called for the new CEO of the National Disability Insurance Agency to be someone with “lived experience” of disability.

Hayes-Brown, the chief executive of a Melbourne disability services organisation, is correct when he writes that “disability is a big tent”. He refers to several impairment categories within disability, which he describes as a “diverse and complex community where lived experience varies greatly”. Hayes-Brown knows about intellectual disability through caring for his daughter, but questions whether he, or anyone for that matter, would be qualified to speak about disability in general merely because they happen to know a lot about their own or about one particular category. This kind of lived experience, he says, is unconscious bias.

So far, so good, but there’s more to it than that. While I know a lot about being deaf, until I became involved in disability quite a few years ago, I bounded up and down steps and stairs without giving them a moment’s thought. I still do the former, but with regard to the latter, at least I now understand the insidious impact of the assumptions that stairways are the best and only means of moving up and down between levels. I can now reproduce that enhanced understanding through a thousand other examples of all kinds of disability categories. You don’t necessarily need the lived experience of disability to gain that understanding. It’s called inclusion, and it’s a lot to do with empathy.

However by a considerable margin, Hayes-Brown falls short in his understanding of “lived experience” of disability. He acknowledges its relevance for your own disability category, but he stops there. His understanding resembles that of lots of little tents inside his very big tent of disability, and no-one really knows what goes on in the other tents. So in his terms, as a deaf person I wouldn’t be able to relate to what it’s like for someone who is autistic, who has epilepsy, or who is part of in-your-face crip culture, for example.

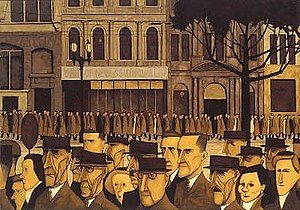

But strangely enough, I can, and it’s because of the polar opposite of inclusion. Regardless of the kind of disability, the universal experience of every person with a disability is the experience of being excluded. It’s the experience of being overlooked, left out, rejected, ignored, dismissed and forgotten. It includes hatred, contempt, and discrimination.

Exclusion never stops

In some shape or form exclusion happens all the time, every day, and it never stops. Exclusion can be something as simple as a lack of captions or audio description on a video. Exclusion ruins an evening when an accessible taxi fails to turn up, causing a person with a disability to miss a family reunion or a long-anticipated date. Exclusion can be as serious as young women with disabilities having hysterectomies without their consent. It happens when violence against women with disabilities is dismissed or trivialised. At the time of writing it’s all over Twitter how Jetstar refused to allow a deafblind woman to travel by herself from Perth to Adelaide. Untold thousands of examples of exclusion happen constantly. Not one of them will ever affect men like Phil Hayes-Brown.

Exclusion is the lived experience of disability. So is fighting it, negotiating it, and gritting your teeth and working out how to get around it. I call this rat cunning. On some days you succeed, on some days nothing works, and on yet other days, you are too exhausted to bother.

But this unrelenting lived experience adds quality to the person you are. Those qualities include resilience, toughness, and for some, artistic expression. These count for something. Exclusion because of disability, because your body happens not to work in a particular way, is an experience that polished insurance executives know nothing about. That’s why it’s vital that NDIS executives know more about disability than textbook theory.

THIS BRINGS ME TO the question of flags. The recent months in Australia have seen celebrations and flag waving for two distinct groups, the LGBTIQ+ community, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. We have had Gay Pride Week, and IDAHOBIT, which takes a stand against the forms of fear against people with diverse forms of sexuality and expression. We have had Reconciliation Week, and Sorry Day, both of which offer a way for Australia to come to terms with its past treatment of Aboriginal peoples. What do these groups have, that people with disabilities have not?

THIS BRINGS ME TO the question of flags. The recent months in Australia have seen celebrations and flag waving for two distinct groups, the LGBTIQ+ community, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. We have had Gay Pride Week, and IDAHOBIT, which takes a stand against the forms of fear against people with diverse forms of sexuality and expression. We have had Reconciliation Week, and Sorry Day, both of which offer a way for Australia to come to terms with its past treatment of Aboriginal peoples. What do these groups have, that people with disabilities have not?

They have flags, colourful, distinctive and iconic flags. No matter where they are flown, they are recognised. Both flags unify groups that are in themselves remarkably diverse. They say to the world, we are made up of many diverse people, each with their own views, but equally, we are all one.

Disability cries out for its own unifying flag. Ideally it would be a flag that captures the unrelenting efforts of people with disabilities and their supporters to make their way in a world that at best is indifferent, and at worst, is hateful.

IT’S EASY TO FALL into the trap of assuming that most people with disabilities slog their way through work that is menial and underpaid. Such a view overlooks the diversity of disability; many with disabilities are professionals, entrepreneurs, innovators and creatives. Of course they are perfectly capable of senior roles in the NDIS, especially those who fly the flag of lived experience, and from this, draw strength.

Leave a Reply