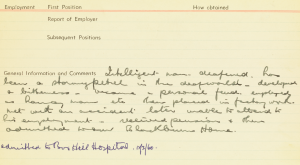

UNIACKE, Mike: Visited him yesterday. Appeared confused, and smelt of the drink. Could not explain his absence from Divine Service for the past month, but promised to start attending. Said I would be keeping an eye on him.

welfare worker.

welfare worker.The Unguarded Quarter Publications

UNIACKE, Mike: Visited him yesterday. Appeared confused, and smelt of the drink. Could not explain his absence from Divine Service for the past month, but promised to start attending. Said I would be keeping an eye on him.

welfare worker.

welfare worker.Michael Uniacke writes frequently on themes around deafness, hearing impairment and disability. He lives in Australia in Melbourne, Victoria, and in Castlemaine in central Victoria. He plays the drums, not very well, and is even worse on bass guitar.

Artwork: John Veeken www.johnveeken.com Maria Von Trapp was prancing about in an Alpine meadow in the Austrian Alps, singing her way into our hearts, … Read On...

Hilarious Michael ! Best wishes Russell Watts